Blind Obedience: Milgram’s Experiment

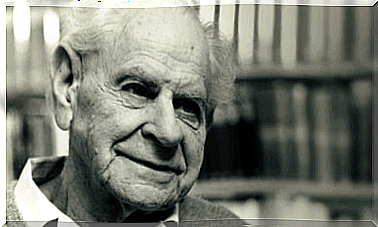

Why does a person obey? What is blind obedience? To what extent will a person follow an order that goes against their values? Stanley Milgram’s experiment (1963) may provide answers to these questions. At least that was his intention.

This experiment is one of the most famous in the history of psychology. It also revolutionizes the ideas we have about people. Most of all , it gives us a powerful explanation of why good people can sometimes be very cruel. Are you ready to learn more about the Milgram experiment on blind obedience?

Milgram’s experiment on blind obedience

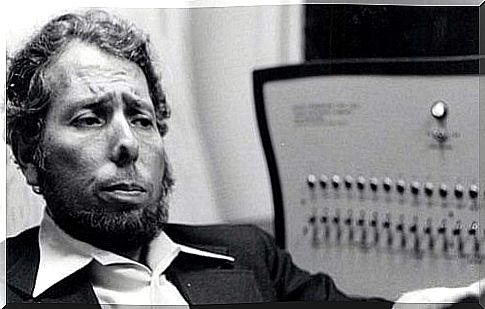

Before we analyze obedience, we will first go into how he conducted the experiment. First, Milgram placed an ad in the newspaper in which he searched for people who would be willing to be paid to participate in a psychological study. When the participants arrived at the laboratory at Yale University , a researcher told them to participate in a study on learning.

In addition, their role in the study was explained to them in this way: they would ask another participant for a list of words to assess memory. But…

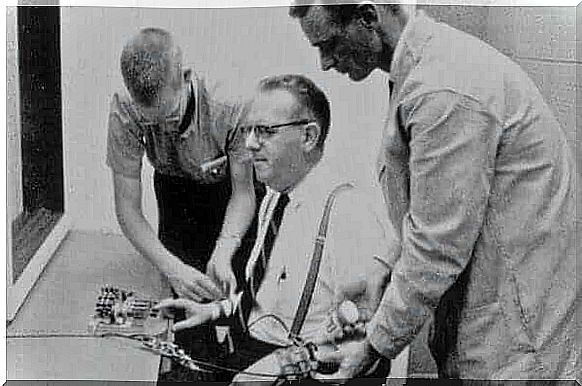

This explanation was a lie that obscured the actual experiment. The participant thought he was asking questions to another participant, but this was actually an employee of the researchers. The participant’s task was to ask the other person for a list of words that he had previously memorized. If he answered correctly, they could move on to the next word. If he answered incorrectly, the participant was told to give the sinner an electric shock (no electric shock was given, but the participant did not know).

The participant was told that the machine that gave the electric shock had 30 levels of intensity. For each mistake the respondent made, the participant had to increase the force of the electric shock. Before the experiment began, the researchers’ sworn collaborators received several small “electric shocks” and expressed how painful it was for the participant.

The course of the experiment

At the beginning of the experiment, the researchers’ co-conspirators correctly answer the participant’s questions without any problems. But eventually the co-conspirator begins to answer incorrectly and the participant must punish him with electric shocks. The participant cannot see the person who receives the electric shocks, but he can hear them. The co-conspirator follows these guidelines: when he is at intensity level 10, he starts complaining about the experiment and wants to quit. At level 15, he refuses to answer and shows that he is determined to oppose the experiment. After they have reached level 20, he will “faint” and therefore be unable to answer more questions.

The researcher who stays with the participant will encourage him to continue the experiment, even after the co-conspirator pretends to faint. The researcher explains that not answering the question is also considered to be the wrong answer. In order for the participant not to be tempted to end the experiment, the researcher reminds the participant that he is obliged to complete and that the researcher is responsible for what happens.

So now I ask you, how many people do you think continued all the way up to the last intensity level (the one that apparently could cause death)? How many do you think reached the level where the conspirator “fainted”? Let’s look at the results of the “obedient criminals” in the experiment.

The results of Milgram’s experiment

Before conducting the experiment, Milgram asked some of his psychiatric colleagues to predict the results. Most participants thought the participants would end the experiment after the co-conspirator had first started complaining. They thought that around 4% would reach the level where the conspirator “faints”. Furthermore, they believed that only one in a thousand participants would reach the last level and that it would indicate a perverse problem (Milgram, 1974).

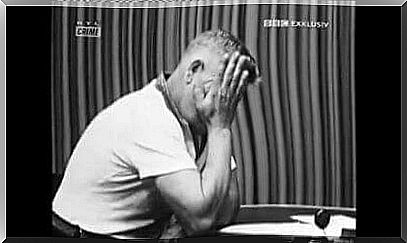

The projections were completely on the ground. Of the 40 participants in the first test round, 25 of them reached the end. At least 90% of the participants reached the level where the co-conspirator “faints” (Milgram, 1974). The participants obeyed the researcher anyway, although some of the participants were clearly very stressed at the thought of harming another person.

Milgram was told that the sample could be biased, but this experiment has been copied with different participants and in different variants as we see in Milgram’s book (2016). All had similar results. A researcher in Munich found that 85 percent of his participants reached the maximum level (Milgram, 2005).

Shanab (1978) and Smith (1998)’s studies show us that the results are likely for any other western country. Nevertheless, we must be careful to believe that we have found a universal social behavior : transcultural research does not show unambiguous results.

The conclusions from the Milgram experiment

The first question we will ask ourselves after seeing these results is, why did people obey all the way up to these levels? What led to blind obedience? In Milgram’s book (2016), there are several write-downs of the participants’ conversations with the researcher. In these we can see that most of the participants felt unwell about their own behavior. Therefore, evil does not motivate them. The answer often lies in the researcher’s “authority” over the participant, where the participant lets the researcher take over all responsibility for what happens.

The influencing factors

Through different variants of the Milgram experiment, the researchers found a number of factors that influenced blind obedience:

- The role of the researcher : the presence of a researcher dressed in a laboratory coat makes the participants look at him as an authority figure. They see his professionalism and are therefore more obedient to his requests.

- Perceived responsibility: by this is meant the responsibility the participant believes he has for his own actions. When the researcher tells the participant that the researcher is responsible for the experiment, the participant does not feel as much responsibility. Therefore, it becomes easier for him to obey.

- The awareness of a hierarchy: the participants who were concerned with hierarchy saw themselves as above the co-conspirator and below the researcher in reputation. Therefore, it became more important to follow the “boss’s” order than to care about the well-being of the conspirator.

- Feeling of a commitment: the fact that the participants had committed to carry out the experiment made it more difficult for them to oppose it.

- Breach of empathy: when the situation forced a depersonalization of the conspirator, it was easier for the participant to lose empathy for him and obey the researcher.

These factors alone will not make a person blindly obey another person, but the sum of them creates a situation where obedience becomes very likely regardless of the consequences. The Milgram experiment shows us an example of the strength of a situation that Zimbardo (2012) talks about. If we are not aware of the strength of our context, this can force us to behave outside of our normal principles.

Blind obedience is possible because the pressure of the above factors is greater than the pressure of the personal conscience. This helps us to explain many historical events, such as the great support for fascist dictatorships in the last century. It also explains more specific cases, such as the behavior and explanations of the doctor who contributed to the extermination of the Jews during World War II.

A sense of obedience

When we see behaviors that do not match our expectations, it is interesting to find out what is causing them. Psychology gives us a very interesting explanation of obedience. One of the most important findings is that a decision made by a competent authority for the purpose of assisting the group has greater consequences than if the decision had been the subject of discussion throughout the group.

Imagine a society under the leadership of an authority that is not criticized, versus a society where the authority figure is constantly tested. Without any control mechanisms, logically the first society will be much faster to follow orders than the last. This is a very important variable that can determine victory or defeat in a conflict situation. This is also closely linked to Tajfel’s social identity theory (1974).

What can we do in the face of blind obedience?

So what can we do in the face of blind obedience? Authority and hierarchy may be flexible in certain contexts, but it does not legitimize blind obedience to an immoral authority. Here we are facing a problem. If we achieve a society in which all authority is scrutinized, we will have a healthy and just society. However, it will fall before other societies in a conflict because it is so slow to make decisions.

If we want to avoid blindly following others on an individual level, it is important to understand that each of us can give in to the pressure of such situations. Because of this, the best defense we have is to be aware of how contextual factors affect us. When these forces threaten to overcome us, we can thus try to regain control and not relinquish responsibilities that belong to us, no matter how great the temptation is to give in to the pressure.

Experiments like this help us reflect on the human condition. They allow us to see that dogmas such as the idea of being good or bad are too black and white to explain our reality. Such experiments are necessary to shed light on the complexity of human behavior and to try to understand the reasons behind it. Knowing this will help us understand our history and not repeat certain actions.

Sources:

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 371-378.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. New York: Harper and Row

Milgram, S. (2005). The scars of obedience. POLIS, Revista Latinoamericana.

Milgram, S., Goitia, J. de, & Bruner, J. (2016). Obesity and authority: the Milgram experiment. Capitan Swing.

Shanab, ME, & Yahya, KA (1978). A cross-cultural study of obedience. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society.

Smith, PB, & Bond, MH (1998). Social psychology across cultures (2nd Edition). Prentice Hall.

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behavior. Social Science Information, 13, 65-93.

Zimbardo, PG (2012). The Lucifer effect: the pork of the maldad.